Research Article - Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health (2022)

Competition Profile of Violence’s made against Health Professionals in Their Activities at Parakou-Nâdali Health Zone, 2021

Gounongbé Ahoya Christophe Fabien1, Mama Cissé Ibrahim1, Akoun Yves Morel1 and Hinson Antoine Vikkey2*2Department of Research and Teaching in Occupational Health and Environment, University of Abomey-Calavi, Abomey-Calavi, Benin

Hinson Antoine Vikkey, Department of Research and Teaching in Occupational Health and Environment, University of Abomey-Calavi, Abomey-Calavi, Benin, Email: hinsvikkey@yahoo.fr

Received: 11-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. JENVOH-22-69032; Editor assigned: 14-Jul-2022, Pre QC No. JENVOH-22-69032 (PQ); Reviewed: 29-Jul-2022, QC No. JENVOH-22-69032; Revised: 03-Aug-2022, Manuscript No. JENVOH-22-69032 (R); Published: 12-Aug-2022

Abstract

Aim: To determine the profile of violence committed against health professionals in their activities within Parakou-N’dali health zone in 2021.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional, descriptive survey with an analytical focus. Data collection lasted from August to mid-September 2021. Data were gathered using a questionnaire. They were then processed and analyzed using Epi-info software. Statistical parameters of central tendency, dispersion and Chi2 were used. The threshold of significance was 5%.

Results: Overall, 259 subjects were surveyed. Response rate was 90.88% and gender ratio (M/F) 0.7. About 56.76% of them were victims of violence. Of the latter, 63.82% were female. The subjects with less than 5 years of seniority (30.12%), those living with a partner (62%) and single ones (46.90%) were more abused. The attendants were responsible for 68.42% of violence cases. The services of pediatrics, gynecology and emergencies were most prey to violence. The most common causes were lack of communication and long waiting times. Midwives (69.70%), orderlies (68%) and nurses (61.68%) were more affected. Violence occurred mostly between 9 pm and 7 am.

Conclusion: Workplace abuse is a major issue for caregivers in the Parakou-N’dali health zone. To prevent it, urgent measures are needed.

Keywords

Violence; Caregivers; Health zone; Parakou-N’dali

Introduction

In order to meet fundamental human needs, people must work. But the workplace is increasingly plagued by scenes of aggression or violence [1]. In any part of the world, millions of people suffer from work-related violence [2]. Workplace violence being attacks in which people are victims of abusive behavior, verbal threats or psychological aggression involving a risk to their safety, health and more generally their well-being [3]. Like any professional sector in contact with the public, the health care sector is particularly affected by this phenomenon, whatever the form of the aggression. Violence is always very badly experienced by those whose duty is to provide care in all circumstances [4].

In France (2007), 39% of health workers were victims of incidents of verbal aggression, and 14% of physical attacks [4]. In the United Kingdom (2007), 25-59% of health care practitioners experienced verbal aggression annually and 1-11% physical abuse [4].

Africa is not immune to violence in the health care environment. In Morocco in 2008, verbal attacks had affected 90.9% of doctors and 80.9% of nurses; physical attacks were made by 40.4% of doctors and 27.3% of nurses [5]. In Mali, 61.7% of health workers in Bamako were aggressed in 2015 [6].

In the northern part of Benin, investigations have not yielded anything on the issue. The lack of research on violence against health professionals in the exercise of their profession in Northern Benin motivated this study.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The study was carried out in the Parakou-N’dali health zone located in Borgou’s department of North Benin. It took place in two public health centers: the University and Departmental Hospital Center (CHUD) of Borgou- Alibori and the Army Training Hospital (HIA) so as in two private centers: Saint Jean de Dieu Hospital of Boko (HEB) and Clinique As de Coeur (CAC) in Parakou.

It was a descriptive, analytical, cross-sectional study of health professionals. Data collection lasted from August to mid-September 2021. The data were collected using a questionnaire during an individual interview. The dependent variable studied was workplace violence in the 12 months preceding the survey. This involved identifying the forms of violence, the perpetrators of the violence, the location of the violence and its causes. The independent variables took into account the age, sex, religion, ethnicity, seniority, and the qualification of the agent, the health training of the agents, the marital situation, the mode of operation, the number of guards per week, and the mode of custody. Only those subjects who gave their free and informed verbal consent were investigated.

The data collected was processed and analyzed using Epi Info version 7.2.3.1. The central trend and dispersion parameters were used to describe the quantitative variables while the proportions with Confidence Intervals (CIs) were studied for the qualitative variables. Pearson and Associates X2 statistical tests were used to study the prevalence of violence in relation to other variables in the study. The significance threshold was 5%.

Compliance with the issues examined in their opinions and decisions was the rule. Confidentiality of the collected data so as anonymity of the completed questionnaires was observed.

Results

At the end of the study, 259 of the 285 health workers approached were surveyed, representing a participation rate of 90.88%. Female subjects were 152 (58.69%) and male subjects 107 (41.31%). This introduces a sex ratio (M/F) equal to 0.7. There were 169 (65.25%) of staff in public health facilities and 90 % (34.75%). Subjects aged 33-39 made up 29.34% of the sample making this age group the most represented. The extreme ages were 18 and 55 (Table 1). Of those interviewed, 147 or 56.76% had experienced at least one incident of violence in their profession in the last 12 months. Among those, 63.82% were women. Of the 169 public sector respondents, 52.10% were assaulted while 65.56% of the 90 surveyed in the private sector were abused.

| Headcounts | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18-25 | 33 | 12,74 |

| 26-32 | 63 | 24,32 |

| 33-39 | 76 | 29,34 |

| 40-47 | 54 | 20,85 |

| 48-55 | 25 | 9,65 |

| >55 | 8 | 3,09 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 140 | 54,05 |

| Widow (wer) | 8 | 3,09 |

| Single | 54 | 20,85 |

| In cohabitation | 50 | 19,31 |

| Divorced | 7 | 2,70 |

| Occupational group | ||

| Physician | 24 | 6,27 |

| Mid-wife | 33 | 12,74 |

| Nurse | 107 | 41,31 |

| Lab technician | 41 | 15,83 |

| Orderlies | 50 | 19,31 |

| Physiotherapist | 4 | 1,54 |

| Seniority | ||

| <5 | 78 | 30,12 |

| 5-10 | 57 | 22,01 |

| 10-15 | 40 | 15,44 |

| 15-20 | 45 | 17,37 |

| 20-25 | 25 | 9,65 |

| 25-30 | 6 | 2,32 |

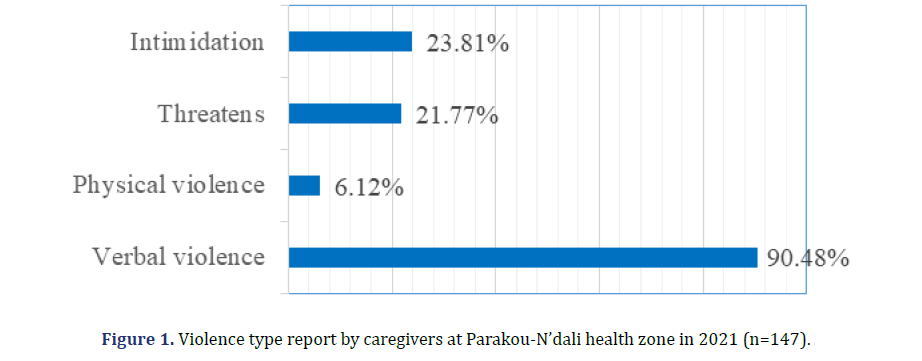

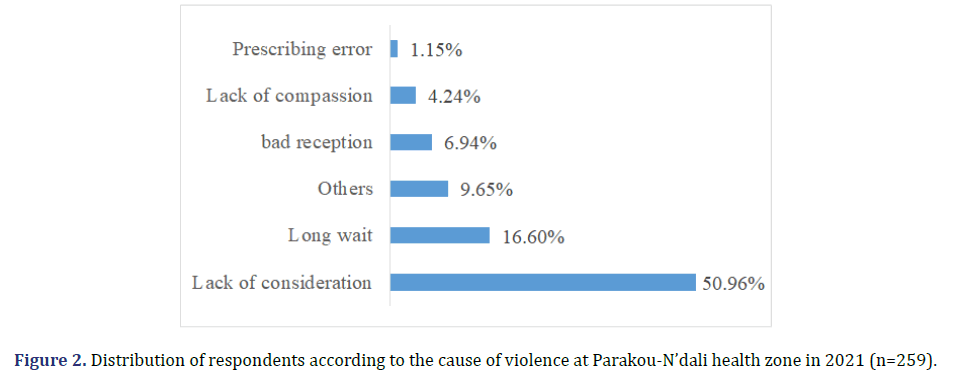

Overall, verbal abuse occurred 90.47% of the time. More affected were those aged 48-55 (72%), those under 5 years of service (30.12%) and those living in a couple (62%). Of all the victims, 30% had informed the hierarchy of their health facility about the involved risks. The remaining results are shown in Tables 2 and 3 and Figure 1. In addition to the physiotherapy department, violence was done to caregivers in all hospital departments, in this case pediatrics (80.56%), gynecology (78.72%), emergencies (76%67%) and psychiatry (75%). Occupational categories most affected were midwives (69.70%), nursing assistants (68%) and nurses (61.68%) (Table 3). Violence was perpetrated in 68.42% of cases by accompanying persons and in 31.58% of patients. The main causes were lack of communication and too long waiting time mentioned respectively by 50.96% and 16.60% of respondents. Acts of violence were mainly committed at night between 9 p.m. and 7 a.m. (Figure 2 and Table 4).

| Violence | Headcounts | Percentage | CI 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Masculine (n=107) | Yes | 50 | 46,73 | 37,02-56,62 |

| No | 57 | 53,27 | 43,38-62,98 | |

| Feminine (n=152) | Yes | 97 | 63,82 | 55,64-71,44 |

| No | 55 | 36,18 | 28,56-44,36 | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married (n=140) | No | 3 | 50 | 11,81-88,19 |

| Yes | 80 | 57,14 | 48,51-65,47 | |

| Widow/er (n=8) | No | 60 | 42,86 | 34,53-51,49 |

| Yes | 5 | 62,50 | 24,49-91,48 | |

| Single (n=54) | No | 3 | 37,50 | 8,52-75,51 |

| Yes | 25 | 46,30 | 32,62-60,39 | |

| No | 29 | 53,70 | 39,61-67,38 | |

| In cohabitation (n=50) | Yes | 31 | 62,00 | 47,17-75,35 |

| No | 19 | 38,00 | 24,65-52,83 | |

| Divorced (n=7) | Yes | 6 | 85,71 | 42,13-99,64 |

| No | 1 | 14,29 | 36-57,87 | |

| Occupational group | ||||

| General practitioner | Yes | 10 | 55,56 | 30,76-78,47 |

| No | 8 | 44,44 | 21,53-69,24 | |

| Medical specialist (n=6) | Yes | 3 | 50 | 11,81-88,19 |

| No | 3 | 50 | 11,81-88,19 | |

| Mid-wife (n=33) | Yes | 23 | 69,70 | 51,29-84,41 |

| No | 10 | 30,30 | 15,59-48,71 | |

| Nurse (n=107) | Yes | 66 | 61,68 | 51,78-70,92 |

| No | 41 | 38,32 | 29,08-48,22 | |

| Lab technician (n=32) | Yes | 6 | 18,75 | 07,21-36,44 |

| No | 26 | 81,25 | 63,56-92,79 | |

| orderlies (n=50) | Yes | 34 | 68,00 | 53,30-80,48 |

| No | 16 | 32,00 | 19,52-46,70 | |

| Radiology technician (n=9) | Yes | 5 | 55,56 | 21,20-86,30 |

| No | 4 | 44,44 | 13,70-78,80 | |

| Physiotherapist | Yes | 0 | 0 | |

| No | 4 | 100 | 39,76-100,00 | |

| Violence | Headcounts | Percentage | CI 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emergencies | Yes | 23 | 76,67 | 34,49-76,81 |

| No | 7 | 23,33 | 9,93-42,28 | |

| Gynecology | Yes | 37 | 78,72 | 64,34-89,30 |

| No | 10 | 21,28 | 10,70-35,66 | |

| Surgery | Yes | 14 | 73,68 | 34,49-76,81 |

| No | 5 | 26,32 | 9,93-42,28 | |

| Internal medicine | Yes | 13 | 56,52 | 34,49-76,81 |

| No | 10 | 43,48 | 23,19-65,51 | |

| Psychiatrics | Yes | 3 | 75 | 19,41-99,37 |

| No | 1 | 25 | 0,63-80,59 | |

| Physiotherapy | Yes | 0 | 0 | |

| No | 4 | 100 | 39,76-100,00 | |

| Laboratory | Yes | 26 | 28.89 | 19,82-39,40 |

| No | 64 | 71.11 | 60,60-80,18 | |

| Pediatrics | Yes | 29 | 80,56 | 8,19-36,02 |

| No | 7 | 19,44 | 10,34-35,26 | |

| ORL | Yes | 0 | 0 | |

| No | 1 | 100 | 2,50-100,00 | |

| Cardiology | Yes | 2 | 66,67 | 9,43-99,16 |

| No | 1 | 33,33 | 0,84-90,57 | |

| Dermatology | Yes | 1 | 50 | 1,26-98,74 |

| No | 1 | 50 | 1,26-98,74 |

| Violence type | Headcounts | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 08 am–08 pm | Verbal | 67 | 45,58 |

| Physical | 5 | 3,40 | |

| Threat | 14 | 9,52 | |

| Bullying | 14 | 9,52 | |

| 09 pm–07 am | Verbal | 111 | 75,51 |

| Physical | 8 | 5,44 | |

| Threat | 27 | 18,37 | |

| Bullying | 30 | 20,41 |

Discussion

This study, carried out in northern Benin to identify violence against health professionals in the exercise of their activity, revealed that 56.76% of those in the Parakou- N’dali health zone were victims of the phenomenon in 2021. Similar results of caregiver violence, reported in 2017 by Abdellah and al (59.7%) in Egypt [7] and by Cheung and al in Macau in 2014 in China [8] which had obtained 59.7% and 57.2% respectively. Assaults were 90.48% verbal in our study. In Jordan, a study led by Al- Omar found in 2015 that 90.8% of nurses had experienced verbal abuse [9]. A slightly higher frequency of 96% had been noted among health workers in Bamako, Mali [6]. In contrast, a study conducted by Abodunrin and Al in Nigeria in 2014 reported a frequency well below 64.6% [10].

Verbal expression of the aggressor’s discontent has prevailed over other forms of violence. The expression is the low rate (6.12%) of physical violence done to our respondents. It is also the expression of restraint in aggressive impulses. In Saudi Arabia, Arar City in 2021, the frequency of physical violence is similar to 5% [11]. In contrast, Ethiopian (2019) and Chinese (2017), caregivers were four times (22%) more physically abused than those in the Parakou-N’Dali area [8,12]. Bullying and threats were among the assaults on health care professionals in the study area at 23% and 21.76%, respectively. Both forms of violence were also perpetrated against health workers in 2015 in Iran, 24.8% and 36.4% respectively [13]. In the Midwest in the United States in 2018, Arnetz and al had a rate of 36.4% of hospital staff who experienced threats [14].

None of our investigators lightened being sexually harassed. But in Gambia, 10% of nurses [15] and Brazil, 9.8% of doctors [16] were victims of this form of violence in the exercise of their profession. Of all occupational categories, midwives were the most violented at work at 69.70% in the study area. In Iran, it was nurses (78.5%) [13].

The prevalence of violence is lower in public health facilities 52% than in private training, i.e. 52.10% and 65.56% respectively, introducing a difference of 13.46%. In Turkey in 2015, a study by Pinar and al [17] revealed a different prevalence of 27.6% in favor of public training. It should be noted that in Benin, state employees are guaranteed to finish their careers there. The only fears are possible transfers to a job located in a locality with difficult living and working conditions.

Generally, the populations of Benin resort to medical care after treatment failures by self-medication and/or after passages in religious circles or even in traditional healers. Thus, medical care is sought at an advanced stage of the disease. In these contexts, situations of aggressiveness towards caregivers are born. These situations are observed to varying degrees in all hospital services. This leads to higher rates of violence in pediatrics, gynecology, emergency departments and psychiatry. Night shifts sometimes face increased demands for care, while their numbers and staffing levels are reduced. The consequence is the increase in violence on nights between 9 pm and 7 am. Ouédraogo and collaborators made the same observations in 2010 in Burkina Faso [18]. According to 56.90% of the respondents, lack of communication was the main cause of violence against them. Lack of communication led to aggression on 64.1% of health professionals in Egypt in 2017 and in Bamako in Mali in 2015 [6,7]. The lack of qualified practitioners in health training promotes an overload of work and the reduction of communication time with care seekers.

Conclusion

Violence at work is found in all public and private health facilities in northern Benin. In these settings, violence was mostly verbal. Lack of communication was the main cause of abuse. Female staffs were most affected. All categories of health professionals had been abused, in these case paramedics. Urgent measures are needed to stem the phenomenon so that health systems can be saved.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- Bureau International du Travail (BIT), Conseil International des Infirmières (CII), Organisation Mondiale de la Santé (OMS), Internationale des Services Publics (ISP). Directives générales sur la violence au travail dans le secteur de la santé, Genève. 2002.

- di-Martino V, Hoel H, Cooper CL. Prévention du harcèlement et de la violence sur le lieu de travail. Office des Publications officielles des Communautés européennes 2003.

- Ladhari N, Fontana L, Faict TW, Gabrillargues D, Millot-Theis B, Schoeffler C, et al. Etude des agressions du personnel du centre hospitalier universitaire de Clermont. Archives des maladies professionnelles et de médecine du travail. 2004; 65:557-563.

- Toutin T, Bénézech M. Le médecin victime dans son exercice quotidien : conduite à tenir pour sa sécurité. Annales médicopsychiatriques. 2007; 165:768-773.

- Acharhabi N, EL-Hamaoui Y, Moussaoui D, Barras O. Violence envers le personnel soignant au centre psychiatrique universitaire Ibn Rochd de Casablanca. Esperance médicale. 2008; 15: 101-103.

- Diarra C. Enquête sur les agressions contre les agents de santé dans les structures sanitaires de Bamako. Médecine: Bamako. 2015; 66.

- Abdellah RF, Salama KM. Prevalence and risk factors of workplace violence against health workers in the emergency department in Ismailia. Pan Afr Med J. 2017; 26:21.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Cheung T, Yip P. Workplace violence towards nurses in Hong Kong: prevalence and correlates. BMC Public Health. 2017; 17:196.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Al-Omar H. Physical and verbal workplace violence against nurses in Jordan. Int Nurs Rev. 2015; 62:111-118.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Abodunrin OL, Adeoye OA, Adeomi AA, Akande TM. Prevalence and forms of violence against health care professionals in a South-Western city, Nigeria. Sky J Med Med Sci. 2014; 2:67-72.

- Zraibi S. Agression et violence envers les professionnels de santé du CHU Mohammed VI de Marrakech. Médecine: Marrakech. 2021; 108.

- Yenealem DG, Woldegebriel MK, Olana AT, Mekonnen TH. Violence at work: determinants & prevalence among health care workers, northwest Ethiopia: an institutional based cross-sectional study. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2019; 31:1-7.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Fallahi-Khoshknab M, Oskouie F, Najafi F, Ghazanfari N, Tamizi Z, Afshani S. Physical violence against health care workers: A nationwide study from Iran. Iran J Nurs Midwifery 2016; 2:232-238.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Arnetz J, Hamblin LE, Soudan S, Arnetz B. Organizational determinants of workplace violence Against Hospital Workers. J Occuper Env Med. 2018; 60: 693-699.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Sisawo J, Ouédraogo SYYA, Huang SL. Workplace violence against nurses in The Gambia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017; 17:311.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Wu JC, Tung TH, Chen PY, Chen YL, Lin YW, Chen FL. Determinants of workplace violence against clinical physicians in hospitals. J Occup Health 2015; 57: 540-547.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Pinar T, Acikel C, Pinar G, Karabulut E, Saygun M, Bariskin E, et al. Workplace Violence in the Health Sector in Turkey: A National Study. J Interpers Violence. 2015; 32:2345-2365.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Ouédraogo V, Ouédraogo D, Ouédraogo T. Violence au travail au CHU de Ouagadougou. 2010.

Copyright: © 2022 The Authors. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/). This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.